One of the credos of backcountry travel is to carry the triad of avalanche rescue gear, a transceiver, shovel and probe, along with the ability to use them effectively. These are rescue tools not safety gear, they do not make you safer. The more efficient and effective these tools are and the better you are with using them, the better your group’s chances of a positive outcome, should you or one of your party be buried in a slide. Communication and practice are needed to this end, along with adhering to the design specs of the technology. Undermining any of these can lead to longer rescue times and harsher consequences for the group and the individual.

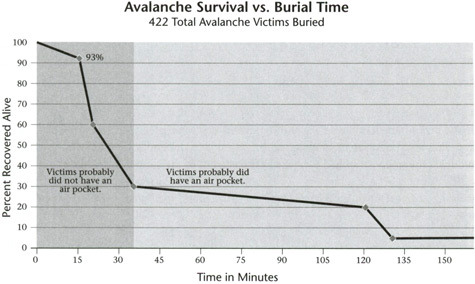

In a rescue situation, time is of the essence. The survivability of being buried decreases dramatically as the seconds and minutes pass. I’ve included a great graph from my favorite avalanche book, Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain, by Bruce Tremper. This is highly recommended reading, I try and read it every season.

What are we searching for when someone is buried? If you said the transceiver, you’re only partially correct. Finding a torso or a leg is great but what we really need to find is THE AIRWAY. The faster we can get to the airway the better chance we have of a survival. The process of getting to this goal is twofold, we find the beacon, then we find the airway. In a recent study Causes of Death Among Avalanche Fatalities in Colorado: a 20-Year Review by Alison Sheets, Dale S. Wang, Spencer Logan and Dale Atkins, from the abstract, “reviewed all avalanche fatalities between 1995 and 2015… Asphyxia was the cause of death in 65% of fatalities… Interpretation: Reducing the occurrence and duration of critical burial, and therefore asphyxia, could have the LARGEST REDUCTION IN FATALITIES.”

Using the transceiver out of specification adds time to the rescue process on multiple levels. Let’s look at each in depth.

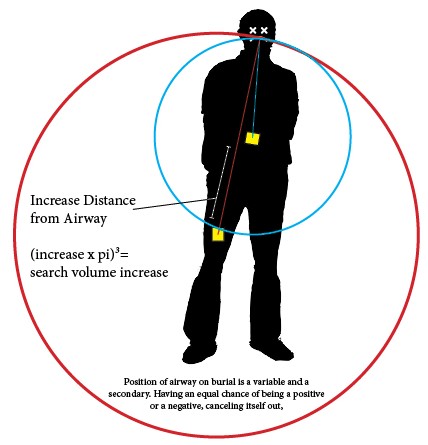

Increasing Search Area

The further away from the airway we carry our transceivers, the larger our search area or more accurately search volume, as we are searching a three dimensional space. The more removed or offset from our true target, the further we must go to that target, through hardened avalanche debris, this may add significant time to breathing life into the victim. To put this in perspective, see how long you can hold your breath.

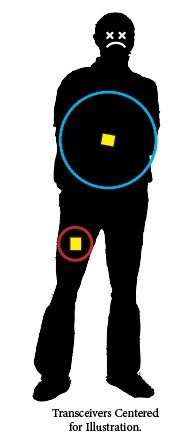

Probe Strike Target

A transceiver placed on the body’s core has a much larger strike area for probing. Since one does not start digging until a positive probe strike, missing the smaller target area of the leg may lead to added time to the commencement of the excavation and arrival at the airway.

Radio Interference

In TRANSMIT mode, the manufacture recommends a 20cm separation for active electronics from the transceiver. With a radio on your shoulder, close to where it is used, a transceiver on your abdomen and a cell phone in your pants pocket all the gear works as designed. There is no need to have a larger separation than this, when transmitting.

In SEARCH mode, the separation should be 50cm, if you are using the unit correctly, the length of your arm easily compensates for this. In addition, the user should turn their cell phones off. Click this link for details on interference. Increasing the transmit separation to 50cm is using the equipment out of specification and is unnecessary and should not be a justification for increasing the distance of the beacon from the airway.

Other Risks

Avalanches can be very violent. It is possible to get stripped in a slide, this could lead to your beacon moving even further from the airway. A harness can prevent this stripping.

Should you use a pocket in your pants, not designed for such use, perhaps attaching the beacon to a belt loop, like a skater’s chain wallet, in an uncontained fashion, the entire transceiver could stripped from the victim. Such user error could end horribly, most likely as a body recovery. Only use beacon designed pants with hardened attachments for the beacon.

The potential increase in rescue time will add time to the overall Hazard Exposure Time, this risk is applied to the entire group from rescuers to the victim(s).

Conclusions – LESS ACCURACY

Moving your beacon away from your airway reduces the accuracy of the very tool that could save your life. There are multiple levels of this reduction in accuracy and this can lead to an increase in rescue time. It’s important to understand all the risks in avalanche terrain, then form an opinion based of your own risk tolerance, we can only mitigate the risks we fully comprehend.

It seems to me that most of the arguments for pocket beacons revolve around comfort and cool factor at least among recreational users. I’m not sure we should be making risk assessments based on these superficial factors. There is also the vest argument amongst patrollers and guides. Vest makers should adapt vests to hold transceivers, with interference distancing accounted for.

The Statistics

Larger Area & Smaller Target & Loss Possibility & Time Increase = Increased Chance of Negative Outcome

Thoughts After Informal Peer Review

I shared this on my personal wall and the Colorado Backcountry Forum on Facebook and here are my takeaways from the arguments presented by users which ranged from recreationalists to professional guides.

As the thread states in the beginning I’m not taking a position either way merely arguing each negative and positive, and I argue each point strongly. There seems to be a fair amount of ambiguity. We have reasons which seem valid for using either method and those reasons diverge for recreationalists and pros/guides. This is not about being right, that notion assumes the issue is black and white, where this is actually about understanding the pluses and minuses and making an informed decision. I have a real problem with just doing what the pros do as the reasons they are doing it one way are not really applicable to what recreationalist do. This concept of toeing the line can lead to groupthink that may lead to harmful decision-making processes, “everyone else is doing it so I will too, I don’t understand why I’m doing it their way but I will do it anyway” Having the conversation in public in the information age gets more viewpoints and that is good in my opinion.

I yield to the many respondents, the concept that strike area should be accounted for by the standard probing method.

I yield that the beacon is not a precise tool.

I cannot yield to the concept that starting further away from the intended goal of the airway is fine. Though my reasoning for this is inductive, if the bulk of deaths are from asphyxia, and our goal is the airway to reduce asphyxia, and we set our target closer to the airway, within reason, we don’t want to get too close or we run the risk of facial injury from probing or radio interference, we should be more likely to get closer to the airway than if we set our target further from the airway. Since it is not deductive reasoning, we cannot be certain of this but if the premises are true there is a good likelihood. The push back on this concept seems to be defensively biased, with arguments resorting to position, failure after location and the need for certainty. The positional data is interesting but to me, it amounts to “the throwing of bones” and divination, it is random since there is no way to correlate or apply the results. This positional occurrence data is misleading and is quite different from say the slope angle occurrence data which ties avalanche occurrence to angle. The seated or standing positions are of potential benefit and occur 31% of the time,

source “Body Positioning of Buried Avalanche Victims.”

Thinking about this from a risk standpoint the negative may occur just shy of 70% of the time, hoping for the beneficial result is optimism since it happens less than half the time, and there is no way to apply it to terrain or angle or position within the slide, ie at the toe, middle, upper, or flanks. So buried positional data should not be a consideration, it is a variable that we should not be optimistic or pessimistic about. There is a 65% chance that the victim will be head downhill, this justifies the step downhill digging strategy mentioned in

THE ABC’s (and D) OF DIGGING: Avalanche Shoveling Distilled to the Basics

One commenter stated “The beacon does not give the ability to know where the airway is, it is not that precise,” and “My bias comes from teaching several hundred avalanche courses and several thousand students. Observing searches makes clear everyone can make the box, and then lose time with poor probing and shoveling. My observations have been validated by Genswein and Edgerly. I have not found any study showing the probe strike was improved by beacon location. Personal preference does not change outcome, just confidence and comfort.”

In response, of course, we cannot know where the airway is from the surface. But through deductive reasoning, we can be certain that the beacon is closer to the airway when on the torso than when in the leg pocket, minus the positional chance of a knee to face burial. The possibility of failure to implement good probing and digging technique after location is a false premise since it demands or assumes user error as a variable against the action. The goal of trying to get closer to the airway from the start is addressed, when you speak of “lose time with poor probing and shoveling,” and if we start everything closer to the airway then there may be a likelihood of less digging and less time loss, inductive reasoning so not a certainty but a likelihood. Unlike an avy class, digging in hardened debris should make us want to hone in on the possibility of getting as close as possible to the airway as we can, even if it’s only a few feet less, time is of the essence.

It would be interesting to see a study developed that used test dummies, both torso and pocket beaconing, thrown separately into avy control routes, perhaps working with CDOT or some other highway unit. Then researchers could locate the victims and dig them out to get data on dig times and exact probe locations in relation to the airway, probe attempts, and the other pertinent data? This would give a sense of how much time was saved or lost in the real-world conditions of refrozen debris. This is more work than I have time for but maybe someone might be interested in it.

People’s need for everything to be neatly spelled out by a study is a bias. The premises of the logic are sound, they do not want to hear them because they don’t come from a study. The closing above also discounts other issues that others see as potentially valid, such as greater exposure to damage and radio interference issues. Perhaps a continuation of bias due to the hypotheses not being contained in a study?

In realms of risk, there can be no certainty and some respondents need for PROOF or certainty is a bit alarming. The need for certainty is delusional and is evidence of bias. If we base decision-making on risk, we know this. If we base decision-making on “safety”, avalanche safety is a paradoxical concept, we are confused by the allusion of certainty the “safe” definition imparts.

Moving to what many agree are the main issues, beacon damage or loss, radio interference, vests, and deployment speed.

Let us start with durability and loss. This news report speaks to the durability issue “Avalanche beacon durability questioned”

https://www.snewsnet.com/…/avalanche-beacon-durability…

and while this particular incident involved a torso placement, it speaks to beacon failure due to damage. A few replies spoke of fabric failures and the potential for ripping the beacon off the leg. I spoke of my experience breaking my phone just tree skiing, while it was in my lower leg beacon pocket. Breaking a beacon requires substantial force, the leg pocket is less secured meaning the beacon can flop around, this could lead to damage to the beacon while skiing or while being transported in an avalanche. Having a beacon secure on the torso does not flop around so there is less likelihood of damaging it while skiing. If you break it from trauma while it is around the torso you may be trending towards a trauma fatality. If you break it while it is on your leg that trauma may be more survivable. But breaking it on your leg seems more likely as it is positionally more exposed.

The top issues for guides seem to be reducing radio interference from high-powered walkie-talkies and speed of deployment unhindered by the radio/tool vest. Radio interference is a serious issue. But does this apply to the recreationalist? The setup I use, a BCA Link 2.0, places the radio unit in the pack and a handset at the shoulder. Using the harness mid-abdomen, I have 40cm of separation from the handset. My phone is in my pant pocket on the opposite side of my body and achieves 40cm of separation, well within 20cm tolerances suggested by the manufacturer for transmit mode. I do not wear a vest, so my beacon is not buried under that hindrance, a nonissue for deployment.

The deployment speed premise is flawed. Someone mentioned a beacon quickdraw contest. Deploying the beacon is not the first response in an avy rescue situation, assessment of the slope’s hazard is. Deployment of the beacon should happen during this assessment. Then with the group in receive mode, you execute the search plan based on that hazard assessment. A guide probably has the wisdom and temperance to whip out the beacon while assessing. A recreationalist might not have that wisdom, whipping out the beacon as fast as possible and jumping in, possibly without assessment. If they get slid as well, the group must deal with an additional victim that is not transmitting. The rescue only becomes a race after the assessment and the plan.

Another couple of concepts brought to our attention by Josh Jespersen was that of the Dirty Pocket, where dirt gets into the beacon and can cause “death lock” where the switching mechanism fails to hold. A solution to this problem would be washing our ski clothes more. We discussed further the idea of the beacon pocket’s positional advantages due to stance, having the beacon on the rear or front leg. It might be time for clothing makers to offer regular and goofy pocket options where the pocket is on the rear leg, in an attempt to minimize impacts.

This is a known issue with Pieps DSPpro switch failure

Josh also mentions some models that have expanded functionality when they are connected to the torso harness. A consideration when choosing the model that’s right for you.

Another aspect to consider is GoPro or other POV cameras and chest placements. These could interfere if the camera is too close to the abdomen placement of the beacon. As an aside chest footage never looks as good as helmet footage, at least in this skier’s completely biased opinion.

Rob Coppolillo “This *might* be a valid point. That said, I’ve had two friends sustain injuries to their chests by having their beacon smashed into their ribs during an avalanche. Pros and cons for sure….” In regards to the concept of studying strike time, strike location, and distance from airway and dig time in real avalanche debris Rob replies, ” That’d be a worthwhile study, for sure.”

Rob adds, “another pro for the pocket is sunny climates (is that everywhere now?!) the top layer(s) comes off and there’s that shiny, expensive, vulnerable beacon bouncing around just below my man-boob. Pocket is maybe a better option in spring, or if you find yourself stripped down a lot.”

So, the question is, does the guide method apply to the recreationalist? It seems like some of the arguments apply and some do not.